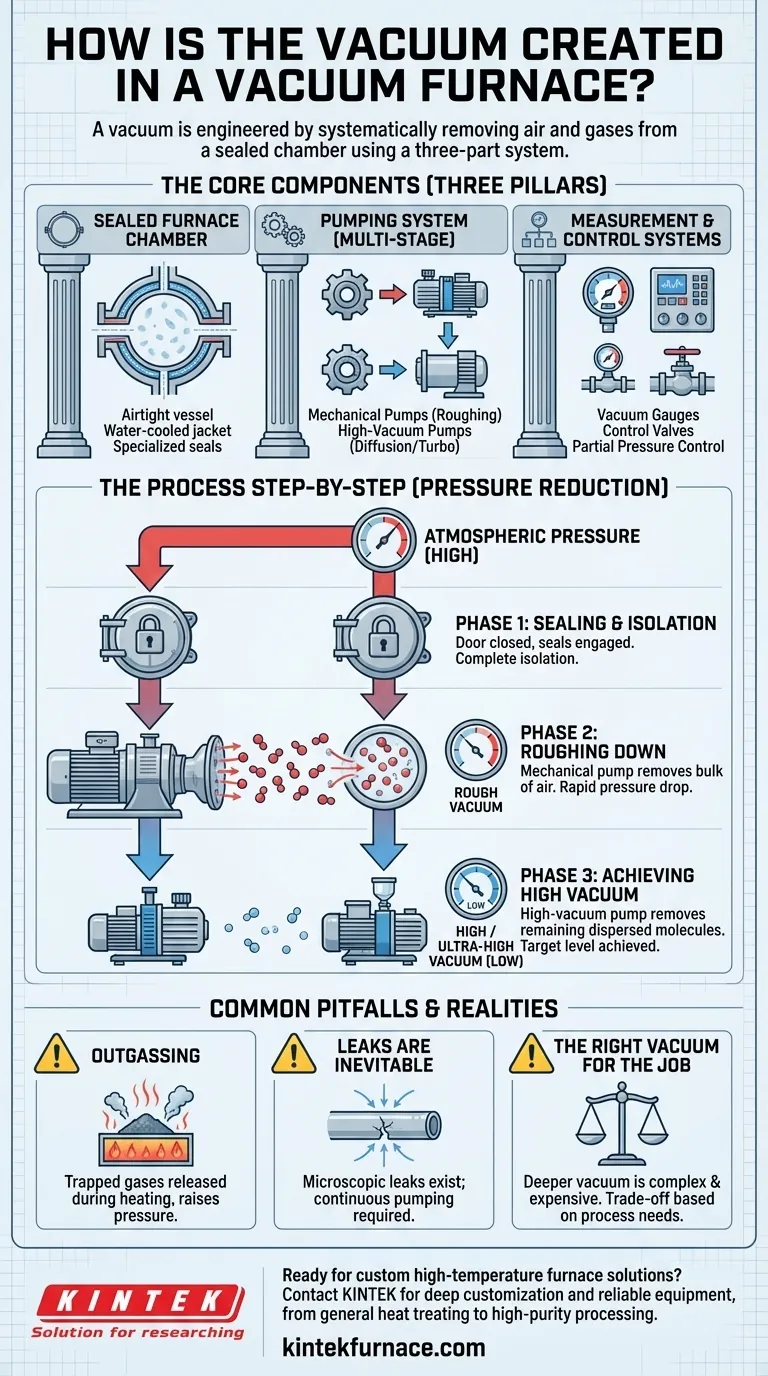

At its core, a vacuum is created in a furnace by systematically removing air and other gases from a sealed chamber using a dedicated vacuum system. This system is comprised of three critical elements: a robustly sealed furnace body, a series of powerful vacuum pumps, and precise measurement and control devices that work in unison to reduce the internal pressure far below that of the normal atmosphere.

Creating a vacuum is not simply about removing air; it is about engineering a highly controlled, sub-atmospheric environment. This is achieved through a multi-stage process that combines physical containment with progressively powerful pumping technologies to achieve the specific conditions required for a given metallurgical process.

The Core Components of a Vacuum System

To understand how a vacuum is formed, you must first understand the three pillars that make it possible: the chamber, the pumps, and the controls. Each plays an indispensable role in achieving and maintaining the vacuum environment.

The Sealed Furnace Chamber

Before any pumping can begin, the environment must be isolated. The furnace body, or chamber, is purpose-built to be an airtight vessel.

It is typically constructed from welded steel plates, often in a double-walled, water-cooled jacket structure. This cooling prevents the shell from deforming under extreme heat, which would compromise the seal.

All removable parts, especially the main door, are fitted with specialized vacuum sealing materials. This physical integrity is the foundation upon which the vacuum is built; without a near-perfect seal, pumps would be fighting a losing battle against constant leaks.

The Pumping System

The pumping system is the engine that drives the evacuation process. It almost always consists of multiple types of pumps working in stages, as no single pump is efficient across the entire pressure range.

The process starts with mechanical pumps (often called "roughing pumps"). These pumps do the initial heavy lifting, removing the vast majority of air from the chamber to achieve a low or "rough" vacuum.

To reach the much lower pressures required for a "high vacuum," a secondary pump takes over. This can be a diffusion pump or a turbo-molecular pump, which can only operate once the initial rough vacuum has been established. The specific combination of pumps is determined by the required vacuum level for the application.

Measurement and Control Systems

Creating a vacuum without being able to measure it is impossible. A vacuum measuring device, or gauge, provides real-time data on the pressure inside the chamber.

This data is used to control vacuum valves, which isolate different parts of the system or regulate the flow of gases. This allows for advanced techniques like partial pressure control, where a specific gas (like argon or nitrogen) is intentionally introduced in small, controlled amounts to achieve a desired effect during the heating process.

Understanding the Pumping Process Step-by-Step

The creation of a vacuum is a sequential operation, moving from atmospheric pressure down to the target vacuum level in distinct phases.

Phase 1: Sealing and Isolation

The process begins by closing and locking the furnace door, engaging all seals. The integrity of these seals is paramount, ensuring the chamber is completely isolated from the outside atmosphere.

Phase 2: Roughing Down

Once sealed, the mechanical roughing pump is activated. It physically removes large volumes of air molecules from the chamber, rapidly lowering the pressure from atmospheric levels (around 760 Torr) down to the rough vacuum range (typically between 1 Torr and 10⁻³ Torr).

Phase 3: Achieving High Vacuum

When the roughing pump reaches its effective limit, it is valved off, and the high-vacuum pump (diffusion or turbo-molecular) is brought online. This pump operates on different principles to capture and remove the far more dispersed gas molecules remaining in the chamber, pushing the pressure down to the high or ultra-high vacuum levels required for sensitive processes.

Common Pitfalls and Technical Realities

Achieving a perfect vacuum is a theoretical ideal. In practice, several factors complicate the process and require constant management.

The Problem of Outgassing

The material being processed and the internal furnace components themselves contain trapped gases. As the furnace heats up under vacuum, these gases are released in a process called outgassing, working against the pumps and raising the internal pressure. Proper process control must account for this gas load.

Leakage Is Inevitable

No seal is absolutely perfect. Microscopic leaks are always present in a complex system of welds, flanges, and seals. A primary function of the pumping system during a process is not just to achieve a vacuum but to continuously pump to overcome the combined rate of outgassing and minor system leaks.

The Right Vacuum for the Job

A deeper vacuum is not always better. Achieving ultra-high vacuum levels is significantly more complex, time-consuming, and expensive. The target vacuum level is always a trade-off between the metallurgical requirements of the process and the practical capabilities of the equipment.

Making the Right Choice for Your Goal

The required vacuum level is dictated entirely by the material and the process being performed.

- If your primary focus is general heat treating like annealing or tempering: A basic system with robust mechanical pumps may be sufficient to prevent oxidation.

- If your primary focus is high-purity brazing or sintering: A multi-stage system with a diffusion or turbo pump is essential to remove reactive gases and ensure joint integrity.

- If your primary focus is processing reactive alloys like titanium or high-temperature alloys: The highest possible vacuum combined with precise partial pressure control is non-negotiable to prevent material contamination and embrittlement.

Ultimately, understanding the vacuum system transforms the furnace from a simple heat source into a precision tool for atmospheric engineering.

Summary Table:

| Component | Role in Vacuum Creation | Key Features |

|---|---|---|

| Sealed Chamber | Isolates environment, prevents leaks | Water-cooled steel, vacuum seals |

| Pumping System | Removes gases in stages | Mechanical roughing pumps, high-vacuum pumps |

| Control Systems | Monitors and regulates pressure | Vacuum gauges, valves for partial pressure |

| Process Steps | Sequential pressure reduction | Roughing, high vacuum phases |

| Common Challenges | Manages real-world limitations | Outgassing, minor leaks, level trade-offs |

Ready to elevate your lab's capabilities with a custom high-temperature furnace solution? At KINTEK, we leverage exceptional R&D and in-house manufacturing to provide advanced solutions like Muffle, Tube, Rotary, Vacuum & Atmosphere Furnaces, and CVD/PECVD Systems. Our strong deep customization capability ensures we precisely meet your unique experimental needs, whether for general heat treating, high-purity brazing, or processing reactive alloys. Contact us today to discuss how we can enhance your metallurgical processes with reliable, tailored equipment!

Visual Guide

Related Products

- Vacuum Heat Treat Furnace with Ceramic Fiber Liner

- Vacuum Heat Treat Sintering Furnace with Pressure for Vacuum Sintering

- Molybdenum Vacuum Heat Treat Furnace

- 2200 ℃ Tungsten Vacuum Heat Treat and Sintering Furnace

- Vacuum Hot Press Furnace Machine Heated Vacuum Press Tube Furnace

People Also Ask

- What is the vacuum heat treatment process? Achieve Superior Surface Quality and Material Performance

- What role does a high-temperature vacuum heat treatment furnace play in LP-DED? Optimize Alloy Integrity Today

- How does a vacuum heat treatment furnace influence Ti-6Al-4V microstructure? Optimize Ductility and Fatigue Resistance

- What are the benefits of vacuum heat treatment? Achieve Superior Metallurgical Control

- What are the proper procedures for handling the furnace door and samples in a vacuum furnace? Ensure Process Integrity & Safety