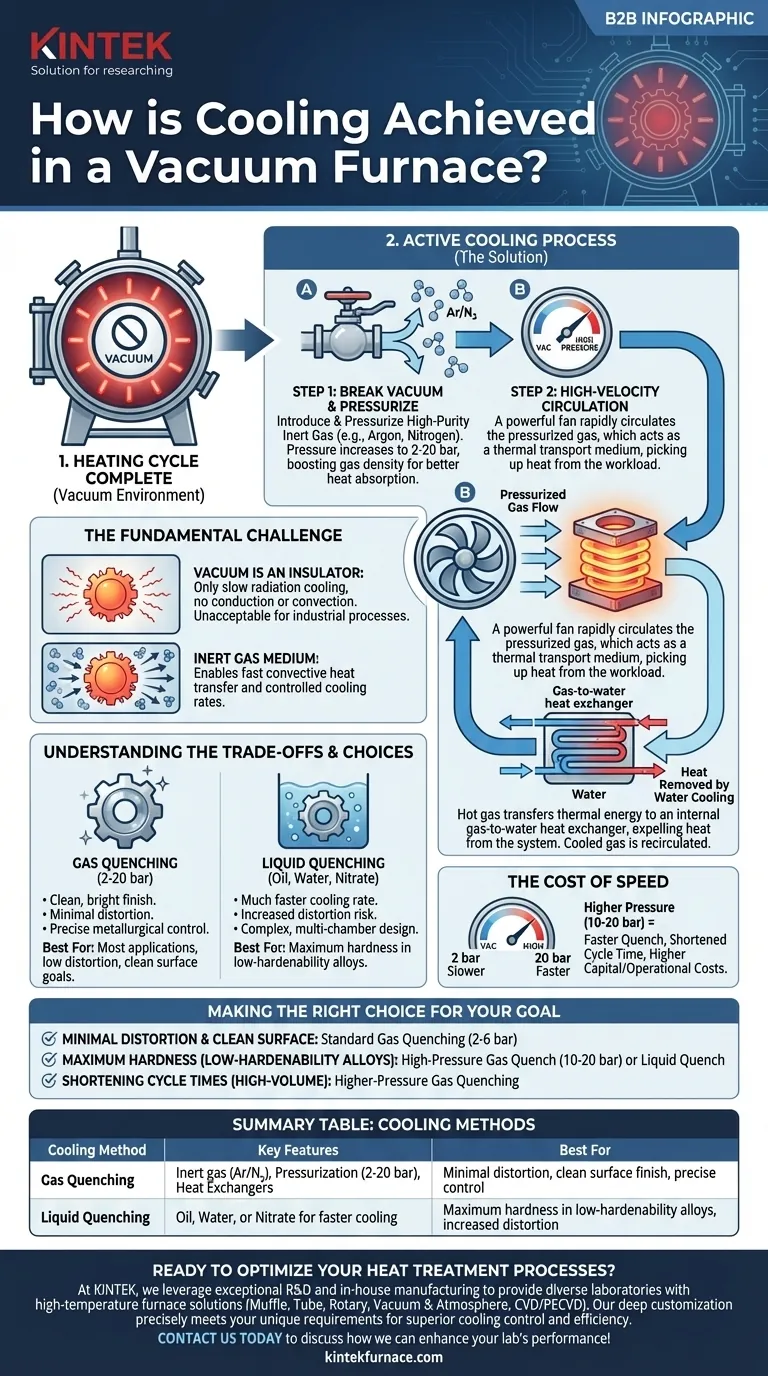

At its core, cooling in a vacuum furnace is achieved by breaking the vacuum and introducing a high-purity inert gas, like argon or nitrogen. This gas is then pressurized and rapidly circulated by a powerful fan, transferring heat from the hot material to an internal heat exchanger, which then expels the thermal energy from the system.

The central challenge of cooling in a vacuum is that vacuum itself is an excellent insulator. Therefore, cooling is an active, engineered process that uses a pressurized inert gas as a thermal transport medium to control the cooling rate and, consequently, the final metallurgical properties of the workpiece.

The Fundamental Challenge: Heat Transfer Without Air

Why You Can't Just 'Cool Down' in a Vacuum

In a normal atmosphere, heat dissipates through conduction, convection, and radiation. A vacuum virtually eliminates conduction and convection, leaving only thermal radiation as a method for a hot object to cool.

This process is extremely slow and provides no meaningful control over the cooling rate, which is unacceptable for most industrial heat treatment processes.

Introducing the Transfer Medium: Inert Gas

To overcome this, an inert gas is introduced into the chamber after the heating cycle is complete. Gases like Argon and Nitrogen are used because they are chemically non-reactive and will not contaminate or react with the hot metal surfaces.

This gas provides the medium necessary for convective heat transfer, acting as a vehicle to carry heat away from the parts.

The Mechanics of Gas Quenching

Step 1: Backfilling and Pressurizing

The first step is to backfill the hot zone with the inert gas. To increase the efficiency of heat transfer, the furnace is often pressurized to levels above the standard atmosphere, commonly ranging from 2 to 20 bar (29 to 290 PSI).

Higher pressure means a higher density of gas molecules, which dramatically increases the capacity of the gas to absorb and transfer heat per unit of volume.

Step 2: High-Velocity Circulation

A powerful, high-temperature fan inside the furnace is activated. This fan circulates the pressurized gas at high velocity through the workload and the entire hot zone.

The moving gas picks up thermal energy directly from the surfaces of the parts being treated.

Step 3: Rejecting Heat via the Heat Exchanger

The now-hot gas is directed away from the workload and through a gas-to-water heat exchanger, which is a standard component of the vacuum furnace.

Cold water flowing through the heat exchanger absorbs the heat from the gas. The cooled gas is then recirculated back into the hot zone by the fan to pick up more heat from the parts. This closed loop continues until the material reaches its target temperature.

Understanding the Trade-offs

Gas Quenching vs. Liquid Quenching

While gas quenching is the most common method in modern vacuum furnaces, other more aggressive methods exist, such as oil, water, or nitrate quenching.

Gas quenching provides a clean, bright part finish and minimizes the risk of distortion. Liquid quenching offers a much faster cooling rate, which is necessary for certain alloys to achieve maximum hardness, but it increases part distortion and requires more complex, multi-chamber furnace designs.

The Cost of Speed

The speed of a gas quench is directly related to the gas pressure. A 10-bar quench is significantly faster than a 2-bar quench, which shortens the overall process cycle time.

However, achieving higher pressures requires a more robust and expensive furnace design, as well as a more powerful circulation fan, leading to higher capital and operational costs. The choice is a direct trade-off between process speed and equipment cost.

Making the Right Choice for Your Goal

Selecting the correct cooling method depends entirely on the material being treated and the desired outcome.

- If your primary focus is minimal distortion and a clean surface finish: Standard inert gas quenching (2-6 bar) is the ideal choice.

- If your primary focus is achieving maximum hardness in low-hardenability alloys: A more severe high-pressure gas quench (10-20 bar) or a separate liquid quench may be required.

- If your primary focus is shortening cycle times for high-volume production: Investing in a furnace with higher-pressure gas quenching capabilities is the most effective strategy.

Ultimately, controlling the cooling process is just as critical as controlling the heating process for achieving precise and repeatable results in vacuum heat treatment.

Summary Table:

| Cooling Method | Key Features | Best For |

|---|---|---|

| Gas Quenching | Uses inert gas (e.g., Argon, Nitrogen), pressurization (2-20 bar), and heat exchangers for controlled cooling | Minimal distortion, clean surface finish, precise metallurgical control |

| Liquid Quenching | Employs oil, water, or nitrate for faster cooling rates | Maximum hardness in low-hardenability alloys, increased distortion risk |

Ready to optimize your heat treatment processes with advanced vacuum furnace solutions? At KINTEK, we leverage exceptional R&D and in-house manufacturing to provide diverse laboratories with high-temperature furnace solutions, including Muffle, Tube, Rotary Furnaces, Vacuum & Atmosphere Furnaces, and CVD/PECVD Systems. Our strong deep customization capability ensures we precisely meet your unique experimental requirements for superior cooling control and efficiency. Contact us today to discuss how we can enhance your lab's performance!

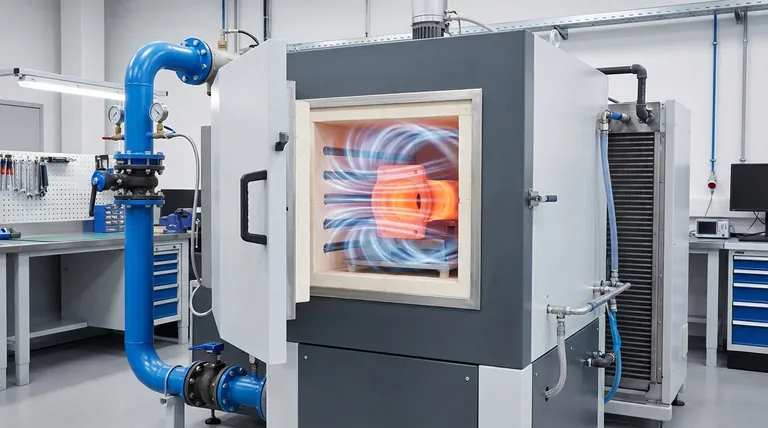

Visual Guide

Related Products

- Vacuum Heat Treat Furnace with Ceramic Fiber Liner

- Vacuum Heat Treat Sintering Furnace with Pressure for Vacuum Sintering

- Molybdenum Vacuum Heat Treat Furnace

- Small Vacuum Heat Treat and Tungsten Wire Sintering Furnace

- 2200 ℃ Tungsten Vacuum Heat Treat and Sintering Furnace

People Also Ask

- What are the proper procedures for handling the furnace door and samples in a vacuum furnace? Ensure Process Integrity & Safety

- What are the benefits of vacuum heat treatment? Achieve Superior Metallurgical Control

- What role does a high-temperature vacuum heat treatment furnace play in TBC post-processing? Enhance Coating Adhesion

- What are the general operational features of a vacuum furnace? Achieve Superior Material Purity & Precision

- What are the functions of a high-vacuum furnace for CoReCr alloys? Achieve Microstructural Precision and Phase Stability