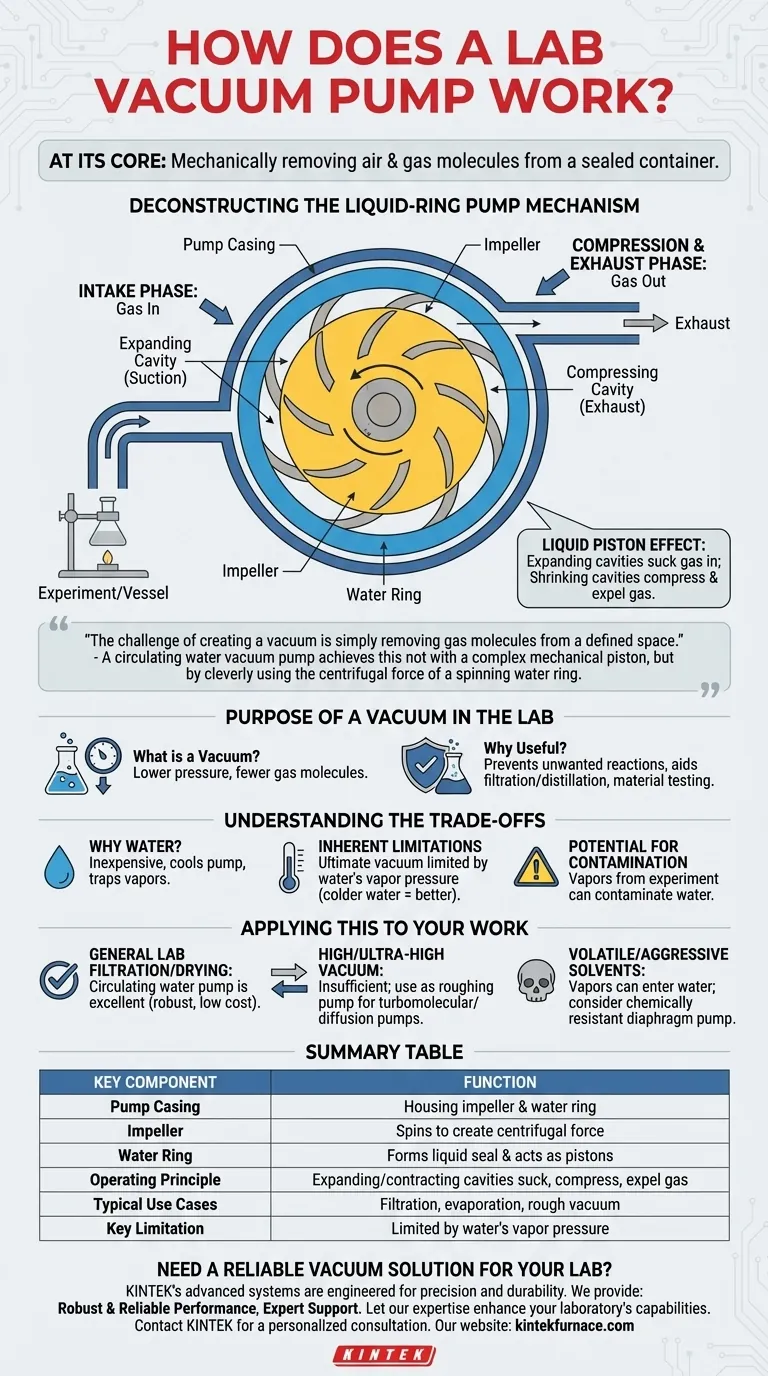

At its core, a lab vacuum pump works by mechanically removing air and other gas molecules from a sealed container. The most common type in a laboratory, a liquid-ring vacuum pump, uses a spinning impeller to create a ring of water inside a cylindrical chamber. Because the impeller is mounted off-center, it creates expanding and contracting pockets between its blades and the water ring, which act like a series of liquid pistons to trap, compress, and expel gas.

The challenge of creating a vacuum is simply removing gas molecules from a defined space. A circulating water vacuum pump achieves this not with a complex mechanical piston, but by cleverly using the centrifugal force of a spinning water ring to create a continuous cycle of suction and compression.

The Purpose of a Vacuum in the Lab

To understand the pump's mechanics, we must first appreciate its goal: creating a low-pressure environment.

What is a Vacuum?

A vacuum is not an empty space but rather a space with significantly fewer gas molecules than the surrounding atmosphere. This reduction in molecules results in a corresponding drop in pressure.

Why is a Vacuum Useful?

Lowering the pressure inside a vessel is critical for many laboratory processes. It can prevent atmospheric gases like oxygen from causing unwanted reactions or contamination, assist with processes like filtration and distillation, or be used for material testing and leak detection.

Deconstructing the Liquid-Ring Pump Mechanism

The circulating water vacuum pump, often called a liquid-ring pump, is a robust and common design that relies on a simple, elegant principle.

The Core Components

The design consists of three primary parts: a cylindrical pump casing, a bladed wheel called an impeller, and a working fluid, which is typically water. Critically, the impeller is mounted eccentrically (off-center) within the casing.

The Role of Centrifugal Force

When the pump is turned on, the impeller spins at high speed. This rotation throws the water outward against the inner wall of the pump casing due to centrifugal force. This forms a stable, spinning ring of water that is concentric with the casing.

The "Liquid Piston" in Action

Because the impeller is off-center, a crescent-shaped void is formed between the central hub of the impeller and the inner surface of the water ring. The impeller's blades divide this space into small, separate cavities. As the impeller rotates, the volume of these cavities changes continuously.

This action creates a "liquid piston" effect in two phases:

- The Intake Phase: As a cavity rotates away from the point where the impeller is closest to the casing, its volume expands. This expansion creates a low-pressure zone, which sucks gas in from the inlet port connected to your experiment.

- The Compression & Exhaust Phase: As the same cavity continues to rotate toward the point of closest approach, its volume shrinks. This compresses the trapped gas, increasing its pressure until it is forced out through the exhaust port.

A Continuous Cycle

This cycle of intake and exhaust happens simultaneously and continuously in each of the cavities between the impeller blades. The constant rotation ensures an ongoing process of suction and expulsion, steadily lowering the pressure in the connected vessel.

Understanding the Trade-offs

While effective, this design has specific characteristics and limitations you must understand to use it properly.

Why Use Water?

Water is an ideal working fluid for general-purpose lab pumps. It is inexpensive, readily available, and effectively cools the pump during operation. It can also condense some vapors pulled from the experimental apparatus, trapping them in the water reservoir.

Inherent Limitations

A liquid-ring pump's ultimate vacuum is limited by the vapor pressure of the water itself. As the system pressure approaches the water's vapor pressure, the water will begin to boil, preventing a deeper vacuum from being achieved. This means performance is better with colder water, which has a lower vapor pressure.

Potential for Contamination

While the vacuum protects your experiment from the atmosphere, vapors from your experiment can be pulled into the pump. These can contaminate the water, which may need to be changed periodically, especially when working with volatile or corrosive solvents.

Applying This to Your Work

Choosing and using a pump effectively depends on understanding its capabilities in the context of your goal.

- If your primary focus is general lab filtration, evaporation, or drying: A circulating water pump is an excellent choice due to its robustness, low cost, and simplicity.

- If your primary focus is achieving a high or ultra-high vacuum: This type of pump is insufficient and must be used as a "roughing" pump in series with a more advanced pump, such as a turbomolecular or diffusion pump.

- If your primary focus is working with volatile or aggressive solvents: Be mindful that vapors can enter the pump's water, and consider a diaphragm pump with chemically resistant components as an alternative.

By understanding the principle of the "liquid piston," you are empowered to operate, maintain, and select the right vacuum pump for your specific scientific objective.

Summary Table:

| Key Component | Function |

|---|---|

| Pump Casing | Cylindrical chamber housing the impeller and water ring. |

| Impeller | Off-center, bladed wheel that spins to create centrifugal force. |

| Water Ring | Forms a liquid seal and acts as a series of pistons. |

| Operating Principle | Expanding and contracting cavities suck in, compress, and expel gas. |

| Typical Use Cases | Filtration, evaporation, drying, rough vacuum applications. |

| Key Limitation | Ultimate vacuum is limited by the vapor pressure of the water. |

Need a Reliable Vacuum Solution for Your Lab?

Understanding the mechanics is the first step; implementing the right equipment is the next. KINTEK's advanced vacuum systems are engineered for precision and durability, ensuring your processes like filtration, distillation, and drying run smoothly and efficiently.

We provide:

- Robust & Reliable Performance: Our systems are built for continuous operation in demanding lab environments.

- Expert Support: Get guidance on selecting and maintaining the perfect vacuum pump for your specific application.

Let our expertise in vacuum technology enhance your laboratory's capabilities.

Contact KINTEK today for a personalized consultation and discover the ideal vacuum solution for your research.

Visual Guide

Related Products

- CF KF Flange Vacuum Electrode Feedthrough Lead Sealing Assembly for Vacuum Systems

- Ultra Vacuum Electrode Feedthrough Connector Flange Power Lead for High Precision Applications

- Small Vacuum Heat Treat and Tungsten Wire Sintering Furnace

- Vacuum Hot Press Furnace Machine for Lamination and Heating

- High Pressure Laboratory Vacuum Tube Furnace Quartz Tubular Furnace

People Also Ask

- Why is sealing critical in vacuum or protective atmosphere furnaces? Ensure Quality and Consistency in High-Temp Processing

- Why is a segmented PID control system necessary for lithium battery vacuum drying? Ensure Precision & Safety

- Why is a laboratory vacuum oven necessary for the processing of Nickel Oxide electrodes? Optimize Solvent Removal

- Why is a high vacuum pumping system necessary for carbon nanotube peapods? Achieve Precise Molecular Encapsulation

- What are the advantages of electric current-assisted TLP bonding? Maximize Efficiency for Inconel 718 Joining